If you want to see some of the greatest art in New York City, steer clear of the museums and the art galleries.

Head instead to the bars, restaurants, skyscraper lobbies, airports and public buildings where the walls are adorned with murals by the likes of Marc Chagall, Roy Lichtenstein, Maxfield Parrish, Keith Haring and other celebrated artists.

“It’s like a museum, except the art collection is scattered around town and not just under one roof,” said Glenn Palmer-Smith, author of “Murals of New City: The Best of New York’s Public Paintings from Bemelmans to Parrish,” a new book with lush photographs from Joshua McHugh and detailed essays documenting the stories behind more than 30 of the city’s important murals.

Some of Palmer-Smith’s favorites may take a little work to find, but many are clustered in midtown, just steps from the shops, restaurants, museums, theaters and attractions likely to be visited by many of 5 million visitors city tourism officials are expecting in town this holiday season.

In Radio City Music Hall, where tourists flock to see the “Radio City Christmas Spectacular,” there are three notable murals. Ezra Winter’s 40-by-60 foot “Quest for the Fountain of Eternal Youth” – a painting Palmer-Smith said was originally “reviled and ridiculed” by critics – is above the main lobby’s grand staircase. “Men without Women,” by Stuart Davis, is in the men’s lounge and, in the women’s lounge, there’s a mural by Japanese painter Yasuo Kuniyoshi that’s based on the flower theme that Georgia O’Keefe had originally created and been commissioned to paint.

The city’s largest mural is Paul César Helleu’s 80,000-square-foot depiction of the constellations in the night sky. It stretches across the ceiling of the main room at Grand Central Terminal and, as it took an amateur astronomer to point out about a month after the terminal opened in 1913, the mural displays the signs of the zodiac in reverse. The mural was restored in 1945 and, after becoming blackened by smoke and city soot, refreshed again in the late 1990s.

When you’re in the terminal, look up in the northwest corner,” said Palmer-Smith, “There’s a patch of the ceiling that was left untouched, so you can see what it looked like before the cleaning.”

Keep looking around the city and you’ll find two murals by Marc Chagall at the Metropolitan Opera, a mural 62-feet tall and more than 35-feet wide by Roy Lichtenstein in the atrium of the Axa Equitable Center (787 Seventh Ave.), Maxfield Parrish’s 30-foot-long mural in the King Cole Bar in the St. Regis Hotel (2 East 55th St.) and work by Keith Haring in several spots around the city.

And then there are the two murals created by Edward Sorel, whose illustrations and caricatures are familiar to readers of The New Yorker and many other magazines. Sorel’s mural in the main dining room of the Monkey Bar in the Hotel Elysée (60 East 54th St.) is populated by a caricatured crowd of celebrities from the 1920s and 1930s, everyone from Isadora Duncan, Joe Lewis and Fats Waller to Frank Sinatra, Ella Fitzgerald, Babe Ruth, Cary Grant and Mae West.

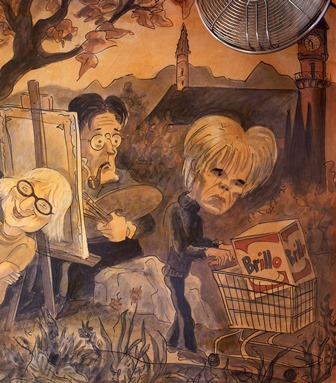

“The Monkey Bar mural is a lot of New Yorkers who were famous celebrities between the first and second World Wars,” said Sorel. “But my favorite is the mural I did for the Waverly Inn in Greenwich Village. That one has caricatures of a lot of the creative, bohemian people who lived in the Village and those people were more interesting to me than the celebrities.”

Forty-three people are portrayed in the mural Sorel created for The Waverly’s dining room, including Allen Ginsberg, Fran Lebowitz, Edgar Allan Poe, Bob Dylan, Norman Mailer and Jack Kerouac.

Public murals “provide a lens through which visitors or viewers can understand the city with some historical perspective,” said Joshua McHugh, the book’s photographer. “Additionally, though, like all successful artworks, these murals create room for dialogue with viewers of any era, helping to make them living and breathing documents.”

Of course, New York isn’t the only city with an impressive collection of publicly accessible murals. Artists hired by the Works Progress Administration during the Great Depression painted murals that remain in post offices, libraries, courthouses and other civic buildings around the country.

And in tiny Toppenish, Washington 75 historically accurate outdoor murals dot a city less than two miles square. Each year, on the first Saturday in June, the Toppenish Mural Society sets up bleachers so onlookers can watch artists complete another mural in just one day.

“People come in the morning to watch the process begin. Then they go grab lunch, maybe look at the other murals in town or visit a winery,” said John Cooper, president and CEO of the Yakima Valley Visitors and Convention Bureau. “They might return in late afternoon to see the end result or just stay and sit and watch the paint dry.”

“Murals are big and bold and beautiful,” said Jane Golden, executive director for Philadelphia’s Mural Arts program, a city where more than 3,600 murals have been created in just the past 30 years, “and a welcome departure from the billboards all around us.”

(My story about murals in NYC – and beyond – first appeared on NBC News Travel in a slightly different form. All photos, except Toppenish, WA by Joshua McHugh.)