While it is now legal to possess and purchase marijuana in Colorado, anyone who brings pot to either of the state’s two busiest airports – Denver International and Colorado Springs – now risks the chance of being fined.

On Wednesday, Denver International Airport held a public hearing to formalize a policy it rolled out earlier in the month prohibiting the possession, use and consumption of marijuana for everyone – travelers, meters and greeters and workers – on airport property.

At the same time, DIA officials announced a set of “administrative citations,” or fines that would be issued as part of that policy: $150 for a first offense, $500 for a second offense and up to $999 for a third offense and beyond.

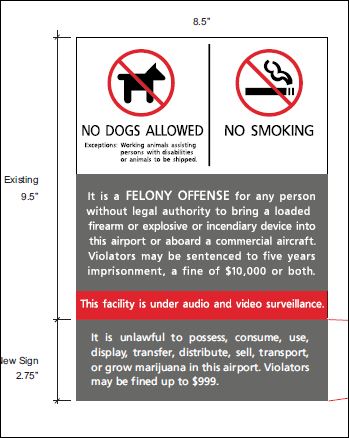

“This is really a last resort for us though,” said DIA spokeswoman Stacey Stegman. “Our primary goal is for people to comply with federal law,” which states that it is illegal to bring marijuana past security or transport it across state lines. See DIA’s new signage below, and then read on.

Stegman said that, as at other airports, if a TSA officer discovers marijuana, local law enforcement is called. “Law enforcement would look at the circumstances and determine what to do—depending upon intent, age, quantity, etc.”

If someone over age 21 is found at DIA airport with a small amount of pot, they’d likely be asked to put it in their vehicle, have someone take it away from the airport or asked to throw it away in a checkpoint trash receptacle. (DIA’s receptacles have lids with small holes, so Stegman isn’t worried about discarded marijuana being retrieved by others.) Those who decline these options would be asked to leave the airport and, before a citation would be given “other options would be explored,” said Stegman.

Signs outlining the rules will be posted at Denver International Airport within seven days, at which time airport and local authorities will begin enforcing the policy.

Starting Friday, January 10, pot is also prohibited throughout Colorado Springs Airport. According to a report in The Gazette, officials have warned the public that possession of pot at the airport could be punishable by a fine of up to $2,500 – and jail time.

Those found with marijuana at the Colorado Springs Airport will have the option to give it up voluntarily, without penalty, by putting it in their cars, giving it to someone to take away from the airport or depositing it in an “amnesty box” to be destroyed.

(My story about pot fine at Colorado Airports first appeared on the Runway Girl Network)