MSP’s award-winning restroom

My “At the Airport” column for USA TODAY this month is all about germs at airports and how crews use high and low tech ways to clean things up.

Here’s a slightly shortened version of that story:

As we head into the busy summer trael season, recent news reports about bed bugs found at Kansas City International Airport and an unscientific but widely-shared ‘study’ highlighting germy spots in airports has many travelers worried they’ll unintentionally pick up something besides snacks and bottled water in the terminals this summer.

Should you worry?

Not about those bedbugs at KCI. The airport was quick to take care of that problem.

And not about that survey which claimed to find high levels of germs on screens at check-in kiosks, gate area chair armrests and water fountain buttons in three unnamed airports.

“It was a poorly designed semi-study with no real science,” said Marilyn Roberts, a professor of environmental and occupational health sciences at the University of Washington’s School of Public Health. “Anywhere there is high hand contact will have lots of bacteria. But unless you are immunocompromised, old, or very young this should not be an issue. We are surrounded by bacteria all the time and the majority are harmless.”

The best way to avoid harmful germs at airports (or anywhere) is – no surprise – to practice good hygiene. “Be mindful about washing your hands with soap and water or alcohol wipes,” said Roberts. And keep hand sanitizer handy.

Travelers will also be reassured to learn how serious most airports are about cleaning and how technology is helping an increasing number of airports maintain restrooms, gate hold rooms and public spaces.

McCarran International Airport in Las Vegas and Pittsburgh International Airport are among the airports that have replaced multiple types of packaged harsh cleaning chemicals with onsite technology and machines that use tap water to create non-toxic cleaning solutions on demand.

In addition to eliminating much of the staff time previously spent purchasing, storing and managing traditional cleaning solutions (and discarding all the packaging), “We’ve replaced six cleaning products with two that allow airport staff to do deeper cleaning without harsh chemicals,” said David Shaw, Vice-President of Facilities and Infrastructure at the Allegheny County Airport Authority, which operates PIT Airport.

Pittsburgh International Airport and Phoenix Sky Harbor International Airport are among airports that have tested autonomous floor scrubbing machines that allow custodial staff to spend more time doing tasks that require more skills and attention. (PIT’s tester came from Nilfisk and Carnegie Robotics; the machine at PHX is by Brain Corp.)

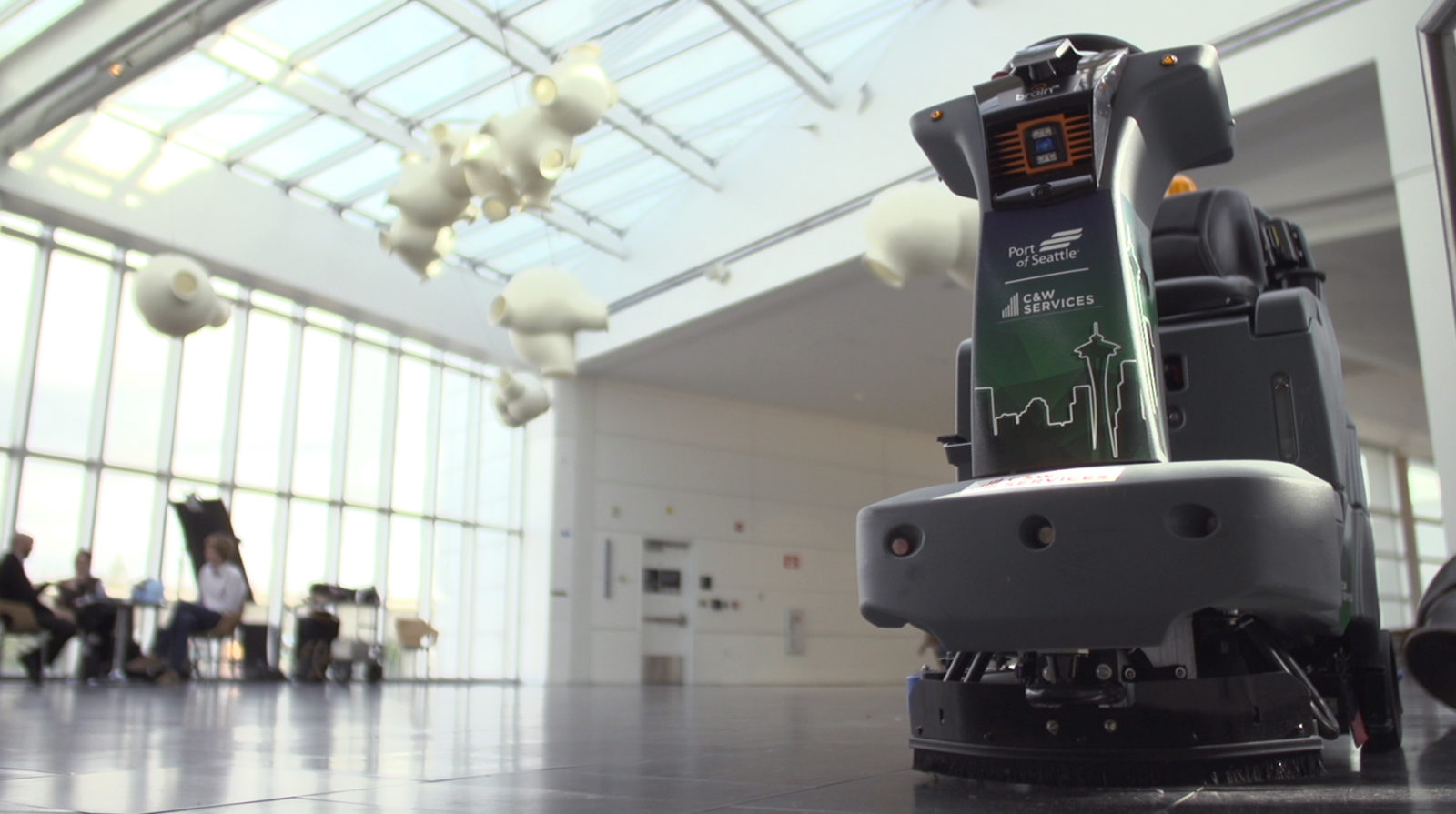

At Seattle-Tacoma International Airport, an automatic floor scrubbing machine is already part of the full-time cleaning team, operating four or five hours overnight polishing high traffic floors and, as a bonus, providing entertainment for late-night passengers.

“It acts like my co-worker,” janitorial worker Jack Lloyd explains in a C& W Services video about the machines, “I set it up, it works and I’m doing something else.”

Laser-focus on the lavatories

Restrooms are among the most highly-visited parts of airports and, in surveys, dirty restrooms are often cited by passengers who are dissatisfied with their airport experience.

In response, airports, which now compete against each other for “Best Passenger Experience” awards, are focusing increased time, attention, and technology on making their restrooms shine.

Their efforts are paying off.

In 2016, the first batch of updated restrooms at Minneapolis-St. Paul International took first place in an annual competition for the Best Restroom in America

High-tech features that helped clinch that award were turbine-powered low-flow fixtures and occupancy sensors that monitor restroom use and signal maintenance crews to clean based on the use and number of visitors, said MSP spokesman Patrick Hogan.

Air is pumped into and out of the MSP restrooms in a way that helps dry surfaces quickly and minimizes odors and digital signs outside the restrooms direct travelers to the nearest open facility when a restroom is closed for cleaning.

Starting in 2016, housekeeping staff at Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky International Airport (CVG) have been wearing Samsung Gear smartwatches and using the TaskWatch app to match staff resources to peak restroom times instead of cleaning restrooms on a set schedule.

Wireless counters at each restroom entrance collect data and once a pre-set threshold is reached an automated message is sent to everyone wearing the watch. “The nearest housekeeper responds, inspects, addresses and clears the alert,” said CVG spokeswoman Mindy Kershner.

Cleanliness scoring for the airport’s restrooms increased so much (7 percent year over year) that what started as a six-month pilot program has been continued.

Now CVG airport is exploring how to use the TaskWatch system in other parts of the airport.

Officials at the Houston Airport system believe detailed attention to maintaining facilities – especially restrooms – that are clean, attractive and accessible, contributed to both George Bush Intercontinental and William P. Hobby earning 4-star ratings last year from Skytrax, a major airport and airline rating service.

“Using the industry clean standards set by the International Sanitary Supply Association, custodial and maintenance staff at both airports work hard to ensure the facilities are maintained at or above those standard levels,” said Bill Begley, Houston Airport System spokesman.

HOU and IAH are also among a growing number of airports nationwide that, like MSP, have ‘smart’ data-gathering programs in restrooms and in other parts of the terminals.

“Everything pushes out data now,” said Tracy Davis, CEO of Atlanta-based Infax, one of the software services companies that collects real time data from passengers and from trash cans, lighting, restrooms fixtures and other things in airports.

“We take that data in and can let airport staff see on a map where there’s a spill or a trash can that needs to be emptied,” said Davis, “We also give maintenance crews predictive information about when flights are due in so they know when restrooms will experience peak hours.”

In addition to high tech tools, airports are also focusing on the basics to keep terminals tidy.

At Seattle-Tacoma International Airport, where that autonomous floor scrubber is earning its keep, airport cleaning crews use cordless vacuums to avoid creating a tripping hazard and use microfiber cloths to constantly wipe down screens on passport control kiosks and common use check-in kiosks.

And SEA Managing Director Lance Lyttle (who previously served as Houston Airport System’s Chief Operating Officer) keeps a plastic glove in his pocket so he’s ready to pick up bits of trash he spots when checking in with his staff in the airport terminal.

Lance Lyttle, Managing Director, Aviation, Port of Seattle, at Sea-Tac Airport, 3 February 2017.

That attention to detail sets a keep-it-clean tone. “It certainly does,” says SEA airport spokesman Perry Cooper, “When the boss does it, you pick up random litter as well.”